Whatever Happened to Starter Homes?

Whatever Happened to Starter Homes?

When World War II ended, Congress passed the GI Bill, which included mortgages with no down payments for veterans. Newly wed vets and their wives were an instant market for "starter" homes, affordable homes built en mass on small plots of former farm land.

Starter homes were the first step on what housing economists would call the "homeownership ladder." As they made each monthly mortgage payment, owners paid down a small part of their loan principal. Simultaneously America's growing population increased their homes' value. Rising values and falling principals quietly increased the ownership stake in their homes, or "equity." When growing families needed more room, they bought more expensive houses and made down payments with money from the sale of their first home. No matter how many times families sold and bought a house, they accumulated equity by moving up the homeownership ladder. When the time came to retire and downsize, many families had accumulated six-figure wealth. Between 1940 and 1960, the fraction of households that owned the homes they occupy increased from 44 to 62 percent,

Homeownership became the way the Greatest and the Baby Boomer Generations acquired "legacy wealth" that they passed along to their children. As a result, many of their children didn't need to save as much proprotonately for their first down payment as their parents. They discovered that the younger they became homeowners and began to climb the homeownership ladder, the better off they would be in retirement. Recent Urban Institute research shows that those who become homeowners at a younger age accrue more housing wealth by their sixties than those who buy their first homes later in life.

The legacy wealth effect perpetuates the racial homeownership gap between White and Black families over generations. A greater percentage of White families than Black families are homeowners and are more likely and more able to help their children with the down payments they need for a first homes.

Home values don't always rise, but owners who weather the hard years still end up better off than renters. According to the Census Bureau, in 2015, just a few years after home values plummeted and created six million foreclosures, homeowners had a median net worth 80 times greater than renters. During better times, such as the four years between 1999 and 2013, the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard found that homeowners gained a median of $91,900 in just four years. The median net worth for homeowners in 2019 was $255,000 compared to $6,300 for renters. That's more than 40 times greater wealth for homeowners compared to those without property in their name.

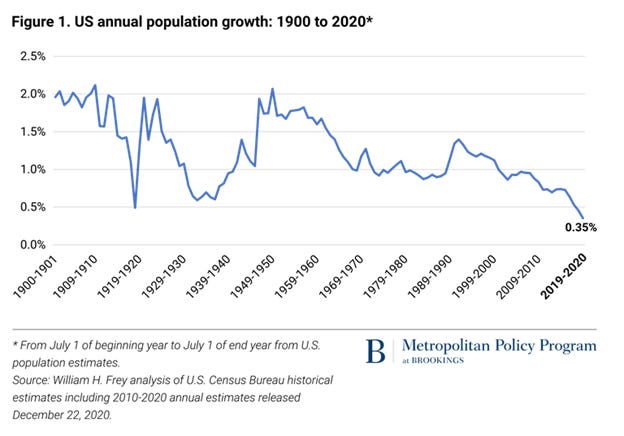

America’s population is growing at the slowest rate in history.

Source: Brookings Institute

Why isn't the homeowneship ladder working today?

Unfortunately, relatively few of today's first-time buyers will come close to achieving the kind of equity growth realized by their parents and grandparents. In 1981, when Boomers were buying their first homes, the median age of first-time homebuyers was between 28-29. A Zillow study found that first-time buyers are renting for six years before becoming homeowners compared to an average of 2.6 years forty years ago. In 2019, the average age of a first-time buyer was 34, the oldest age on record. First-time buyers are waiting so long to save up enough to buy a home that nearly one out of five Millennials has given up on homeownership.

Simply put, the homeownership ladder isn't working anymore. The national economy is growing, but the homeownership rate is not. The reason is not the economy, the size of the population or the desire of young families to become homeowners. The problem is that there are not enough starter homes available for first-time buyers to take the first step up the ladder.

Starter homes of the post-war era were inexpensive because they were built on former farmland with cookie-cutter designs. The post-war boom created acres of single-family homes on small lots. By the later 1970s, In the late 1970s, when Boomers were buying their first homes. The construction of new entry-level homes averaged 418,000 units per year. But mortgage rates were high, and the entry-level housing supply fell by more than 100,000 units to 314,000, according to Freddie Mac's chief economist, Sam Khater.

As time passed, the entry-level supply continued to decline, dropping to 207,000 units a year during the 1990s. Even at its cyclical peak during the 2000s, entry-level supply reached only 186,000 in 2004. "While in 2020 only 65,000 entry-level homes were completed, there were 2.38 million first-time homebuyers that purchased homes. Not all renters looking to purchase their first home were in the market for entry-level homes, however, the large disparity illustrates the significant and rapidly widening gap between entry-level supply and demand," wrote Khater in an April 15, 2021 op-ed.

According to preliminary results of the 2020 Census, the national population is nearly stagnant. Over the past decade, the nation grew by just 0.35 percent, the lowest annual growth rate since at least 1900. The children of the Millennials may create another population bump in the decade to come. In the decade or so before those children reach homebuying age, the nation will have a breathing space to come up with a cure for the ailing housing ladder and the American dream of homeownership.

Land for new home construction is increasingly expensive and less available. Severe shortages of building materials and skilled labor drive new home construction costs ever higher. Can we create enough affordable starter homes to make the housing ladder work for the next generation, or will the homeownership ladder go the way of the horse and carriage?